|

|

|

This review page is supported in part by the sponsor whose ad is displayed above

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reviewer: Edward Barker

Source Analog: Scheu Premier II/Schroeder DPS/Allaerts MC1B Mk 2 & Ortofon SMG 212/EMT micro mono and Teres battery power supply; Garrard 301/Hadcock 242 SE/Music Maker III & Audiomeca Model 1 with Music Maker II; Systemdek Transcription turntable; Thorens 32O turntable with Mission 774/Empire MC1000 among other turntables

Source digital: Copland 288

Phono Amplification: Tom Evans Groove Plus; prototype valve phonostage; Loricraft Missing Link II; Gram Slee Mk 5; Gram Slee ERA Gold

Preamplifier: Canary 803 four box preamplifier with dual mono valve power supplies/NOS valves

Power amplifier: Rogue Audio M150s with NOS Siemens EL 34s; BBC AM84A monoblocks

Speakers: Mårten Design Coltrane Altos; Living Voice OBXR2 [on extended loan]; Isophon vintage open baffle three way

Cables: Silver Arrow, Clearlight Audio NFT, Jorma Design, PHY

Review component retail: $995

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A friend recently pointed out that he thought I was "chasing for the holy grail" of audio. One day I'd surely come to my senses and realize that of course it didn't exist. Naturally, I countered with the standard truism about it all being "in the journey, hello?" Most certainly, I do believe that. At the same time, there's huge pleasure in the unknown, in looking to realize whatever ideal we currently hold. It's the summit syndrome, isn't it? All audiophiles are virtual climbers. We don't know where it is but keep climbing - with Escher-like results. We reach Krell Col and see the ice-swept Wilson Ridge with the silvery sheet of snow arcing like a wave off it. That one is going to be tough. The ascent party asks for volunteers and two men set off, oxygen masks and all. The rest continue, looking for an easier ascent to the summit.

And we reach it. We think we are at the top. After a while, we realize that what looked like a descent is actually going up. So we set off again only to find our Wilson Col friends on their way down but climbing hard, insisting what we see as an early base camp of our own expedition is actually the real summit, the top of Everest itself. Meanwhile we think the lack of oxygen on Wilson Col has gone to their heads.

To some extent, this changing of the landscape underneath us is inevitable. Our tastes and musical requirements are changing too, hopefully becoming more sophisticated but certainly always dictated by our personal need for musical satisfaction. After all, what we are really trying to do in all this madness is get closer to the music.

So he was wrong, my friend was. I did "find the Grail" the other day. I found it of course exactly where Harry Pearson had said all along it would be. That's right: live unamplified music. I can't tell you exactly what was special about this particular occasion from an audio point of view but it might have been because I knew the room well and it was a simple affair. The auditorium was a studio about 25" x 18" x14", with an arched ceiling and completely paneled in wood. It has excellent acoustics. We were an audience of about 25 people, invited for a performance of Schubert's Die Schöne Müllerin (The fair miller maid), D.795, op. 25 (1823). A baritone accompanied by a lone Mini Grand piano sang this lieder cycle. Fine music indeed. However, what was really astonishing were the acoustics.

|

|

|

|

|

I've given a party in this room, with loud disco music. That long-ago night was nothing -- and I mean nothing -- as loud as this baritone in full flight. He was so loud, my eardrums started aching during several passages (and others reported the same afterwards). On top of the sheer SPL factor, the voice caused some phasing problems in the room during peaks. If the sound had been amplified, we'd immediately have suspected bass nodes and started moving the speakers. But he was moving around a bit and turning from side to side. The phasing had little or nothing to do with his placement. The problem had something to do with certain notes but essentially, it was no surprise that the room would be having problems containing that much sound. In fact, one door remained partially open and at full throttle, his voice was still at normal level across the street. My own fair miller's maid said later that she thought the baritone was holding well back and could have gone a lot louder still. (As an aside, do you also have a problem about what to call the person you're married to? Wife is a non-survivable term over here in England and I can't stomach partner or significant other though I do occasionally default to the cockney 'er indoors. Suggestions welcome).

Not that I should have been surprised by any of this. We used to have an acoustic band that rehearsed unamplified in our building. It was amazing how loud 8 instruments got - way beyond what pretty much anyone would consider tolerable, certainly on a regular basis.

Anyway, that evening with the baritone and piano, the sound by definition couldn't have been better. Or could it? In fact, the piano did sound a bit grainy and "solid state". There were subtle veils and a slight absence of dynamics and PRaT in the upper bass department... but seriously, the thing is, HP is right. The reality check for audio is nothing more or less than reality itself. Because it's so easy to do, it's crazy not to. Mind you now, exactly what the point is of going to hear a symphony for comparison is beyond me. A stadium rock concert is equally silly. But a small acoustic band, a jazz trio, a quartet in a church, even a singer in the subway? They can teach us a lot about where we are trying to get to. Or what about that accordion you've got stashed away in the attic?

One of the key qualities that seem to stay as a fixed point of reference during my audio journey has something to do with effortlessness. It's the sensation of being relaxed yet alert at the same time. It has to do with a lack of strain, something with sounding natural and organic rather than artificial and forced. I don't like etched if it's not in the recording. Certain solid-state amplifiers and CDPs suffer from this quality and while it's great to dance to in a disco, it stops me listening to music.

|

|

|

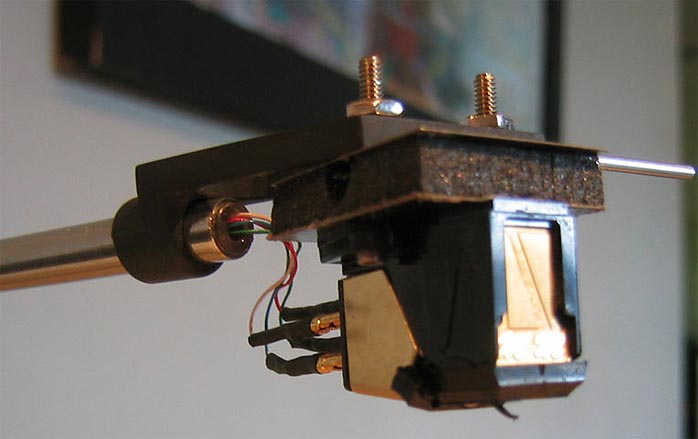

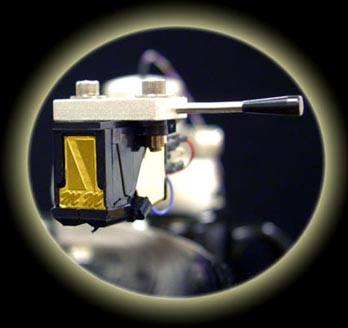

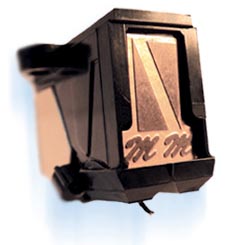

This effortless quality is the first thing that drew me to the Music Maker cartridge. The MM has been a daily companion for the last several years and is now in its third iteration. I feel I know it really well. The last few times I guessed it was playing in a room at an audio show, I got it right. Not that I'm in any way good at blind guessing but this cartridge has got a definite sonic signature. Once you've locked on it, it's pretty easy to identify. If you walk into a room and say "wow, this sounds unforced like the music is just billowing out rather than being reproduced," chances are you could well be near a Music Maker III. And it's a seductive sound. Once you've lived with it, it's very hard to let go of. In other words, it's putting the music rather than its own fireworks first.

|

|

| Explains the website that this cartridge is a "performance variable reluctance device employing a proprietary extended contact diamond stylus." Specifications include an output voltage of 4mV; frequency response of 10Hz - 50KHz; stereo separation of >25dB across 10Hz to |

|

30KHz; loading requirement of 47K just as any standard moving magnet cartridge; weight of 6.2g; stylus type as a proprietary extended contact area diamond; tracking force of 1.58g +/- 0.05g (critical); arm requirement of medium to low mass (13g or less); and with minimal bias (anti-skate) requirements. UK price is £ 625 inclusive of VAT.

So what's the difference between the Mk. II and III? The changes are evolutionary rather than a redesign. Designer Leonard Gregory has been looking at the makeup of his patented line contact stylus and the result is really quite remarkable. With good-quality clean vinyl, we get a CD-type absence of crackles and pops. Background noise becomes inaudible even at high volumes. At the moment, I'm listening to Earl Klugh's Soda Fountain Shuffle, which like most of my records was bought second hand and probably wasn't well treated before I got it. After a wash with the Knosti record cleaner and read with the Music Maker III, the only reason for thinking it's not being played back on CD during a blind test is because of the better sound quality. Even the silent grooves between songs are pitch-black quiet. Extraordinary really. The II's stylus was particularly successful at defining female vocal sibilants (these often seem a good test for a cartridge along with single guitar note bursts with lots of dynamics and overtones in them). I'm also a big fan of the Van Den Hul and Fritz Geyger styluses but this one has something special about it.

The III's Grado Variable Reluctance design remains the same but internal isolation, damping and suspension have been significantly improved. The new combination of design, suspension and stylus shape make this cartridge my contender for "best in the tracking department" of any cartridge I've heard.

|

|

| Occasionally, we run across situations where a product has been improved from a technical point of view but sonically loses something about what made it special. In this case, this hasn't happened. What we get is simply a series of significant gains with no discernable losses. The gains are all in the hifi area as opposed to the musical zone. That's perfect since I'm not convinced it can get musically any righter. What we gain is greater separation and definition of instruments plus enhanced dynamic speed. This of course translates directly into deeper and more vivid tonal color. What we gain most in the end is a kind of ineffable authority, a "just listen to this" quality. Take the organ. It's incredibly difficult to reproduce credibly. There's a great Opus 3 recording [8202 Olsson, Gjorgren Guilmant] where the harmonics are so complex that you're constantly vacillating between believing that an individual note or a chord is being played. It's not just a devil to track; it's also really tough to get a believable organ out of an audio system. (There are countless organ freaks in the UK and it seems they all have Garrard 301s - a diehard combo just like Harleys and Hells Angels). Anyway, the MMIII exudes more of this authority than the II did. Combined with a good turntable and arm, it will make that organ sound like it's moved into your living room or you've moved in with it. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

But reproducing credible organs is not the MMIII's main point. On Leonard Cohen's 10 New Songs [Columbia 85953 ], the cartridge perfectly reveals that smooth relaxed silkiness caught inside the resonances of Leonard's gravelly harmonizing. His voice is truly complex, with tiny shifts in emphasis and rhythmical elongations. His performance is astonishing but it will take a cartridge of the MMIII's caliber to bring out just exactly how amazing he is. This silkiness combined with an unforced openness are defining characteristics of the Music Maker, particularly in its third iteration. That's not to say the cartridge is in any way laid back or bland. Far from it. It's excellent at defining the edges of sounds and when called for, can be as vivid and piercing as many moving coils.

|

|

|

|

|

By a stroke of luck, I managed to have two Music Maker IIIs here at the same time. I mounted them on my Garrard/Hadcock 242 and Scheu/Schroeder DPS table/arm combos respectively, accessed through the same phono stage. An interesting lesson it was, too. In actual fact, the results were by no means definitive as I didn't have the time to set up the second cartridge properly by ear and so probably didn't get the potentially best out of it. (Aside No.2: yes, it's completely true, the MMIII is a tough learning curve to set up but frankly, anything it's competing against is going to be a bear to dial in just the same. For proper calibration, you need time and patience. What's great about the MM3 is how it will show you, slowly, what the right direction is to move towards). Most interesting in this juxtaposition between two different tables and arms was how the signature of the MM3 remained amongst the most standout qualities I heard. This authoritative effortlessness came through regardless of which turntable/arm combo I used.

There's been considerable debate about just how good the MM3 is in absolute terms. Does it really measure up to the finest moving coils? Some people think so, others do not. So much is down to personal taste and turntable/arm/phono stage preferences. The fact is, it doesn't really matter all that much for the very simple reason that pretty much anyone who runs a top-of-the-range moving coil is going to have more than one cartridge - and the MM3 is the natural choice for a partner. It's not just because as an interpreter of music, the MM3 is hard to significantly better. It's also very different to a moving coil presentation, with the added advantage of presenting a completely different vantage point onto the sonic landscape. Having a good MC and the MMIII is a bit like being able to change from horn speakers to electrostats. Which is just one reason why I personally would rather run a MM3 rather than, say the Lyra Dorian or any other fine but not 'statement' moving coil. With the MM3, I don't really feel I'm missing anything because the scenery looks different.

|

|

In pure audio terms, coming up with my own opinion is a problem because unfortunately, my Tom Evans Audio Design Groove Plus does not support moving-magnet settings. I'm pretty sure that what I'm hearing on the best in-house phono stage that will play both my Allaerts MC1B mk2 and the MM3 is the limitation of the phono stage itself. The unit in question is a pretty fancy prototype creature with C-core transformers, valved power supply and separate valve circuits for MM and MC. It's quiet as well. But it's not in the same league as the Groove Plus.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| And here's another aside. I think my version of the Groove Plus is about a year old. I'm not sure exactly what's happened but recently it's gotten a lot -- and I mean a big lot -- more amazing than it used to be. I added ferrites to both ends of each wire and put the power supply on an isolation shelf but in the end, it's probably more to do with running in than anything else. The thing suddenly began to sound like it was on steroids. Whereas six months ago the valved prototype sounded close if not quite as good, now the valve unit sounds the same or slightly better due to extended break-in but the Groove Plus operates in a different league altogether. In its new guise, the Groove + |

|

is not just the reining monarch among the phono stages I've heard to date; it also makes my valve prototype sound almost grainy. That, my friends, takes some doing. There's a vividness, depth of stage and instrumental separation plus a piercing, fiery quality to the highs with the Groove Plus that once lived with is difficult if not impossible to do without.

Anyway, I would dearly like to hear the MM3 on a TEAD Groove Plus. If I did, I would by no means be surprised if it got me off the ruinously expensive habit of chasing the Allaerts dragon. Until I get a moving-magnet Groove Plus, I'll have to suspend judgment about how ultimately and objectively good this cartridge can get. In my own reality, I don't think I could live without either the MM3 or the Allaerts, the point being though, who cares? If you love music, you're going to want a non-ruinously expensive cartridge to live with and play music so you can, if you want to, play it all day. Doing so with openness, generosity of sound and a wonderfully expressive musical ear at a relatively affordable price is quite something. If you know of another cartridge out there that can pull the same tricks, please let me know. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|